06/10/2021

The Journalist House in a Storm of Conflict; Research paper on Implementing more Sustainable and Protection Strategies

This report addresses the work of the SCM Journalist House project that supported Syrian media professionals and human rights advocates over the last four years (2017-2020).

The report classifies the support applications received by the SCM into nine categories. In each category, there are details about the number of applications received inside and outside Syria, the number of supported applications, and their types and percentages by category and gender. The report also reviews the beneficiaries’ feedback on the provided support including their priorities reflected in the figures and data analysis. It also identifies the reasons behind weak support and makes recommendations to improve it and enhance its sustainability.

The report adopted the quantitative, statistical, and descriptive approach by analyzing the data of the «support application forms» received by the SCM between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2020. The numbers of all (accepted, rejected, and supported) applications were extracted from the SPD and classified under nine categories.

“The Journalist House in a Storm of Conflict”

Research Paper on Implementing More Sustainable Support and Protection Strategies

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression

January 1, 2017 – December 31, 2020

I- Summary

This report addresses the work of the SCM Journalist House project that supported Syrian media professionals and human rights advocates over the last four years (2017-2020).

The report classifies the support applications received by the SCM into nine categories. In each category, there are details about the number of applications received inside and outside Syria, number of supported applications, and their types and percentages by category and gender. The report also reviews the beneficiaries’ feedback on the provided support including their priorities reflected in the figures and data analysis. It also identifies the reasons behind weak support and makes recommendations to improve it and enhance its sustainability.

Based on the database of the Support and Protection Department (SPD) in the SCM Journalist House Program, the support applications received from individuals and institutions were grouped under nine categories:

- Livelihood

- Medical

- Asylum

- Safe relocation

- Job opportunities

- Technical support and press cards

- Legal

- Advocacy

1- Support to individuals:

In the period between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2020, the SCM received 2,165 support applications of different categories (1,347 from inside Syria, 592 from Arab and foreign countries and the emergency funds received 226 applications).

The SCM received 608 livelihood support applications, of which 135 ones were funded by international institutions; 54 medical support applications, of which 27 ones were supported; 168 technical support and press cards applications, of which only five were supported; 19 legal and advocacy support applications, of which 12 ones were supported; 89 jobs support applications, of which 54 ones got direct support from the SCM. It also received 225 safe relocation support applications, of which 43 were supported; 719 asylum applications, of which 199 were supported; 57 other support applications, of which only three were supported.

Based on the SCM conviction in the importance of supporting the empowerment approaches focusing on women participation, gender equality and management of diversity and difference, the categorization of applications was gender-sensitive. 20.72% of the accepted applications were submitted by females and 79.2% by males.

In addition, the SCM carried out a beneficiary satisfaction assessment which covered 102 supported Syrian media workers. 85% of them responded and 47% expressed enormous satisfaction with the support they received. 38.8% considered the safe relocation support a priority and 20.8% prioritized technical support.

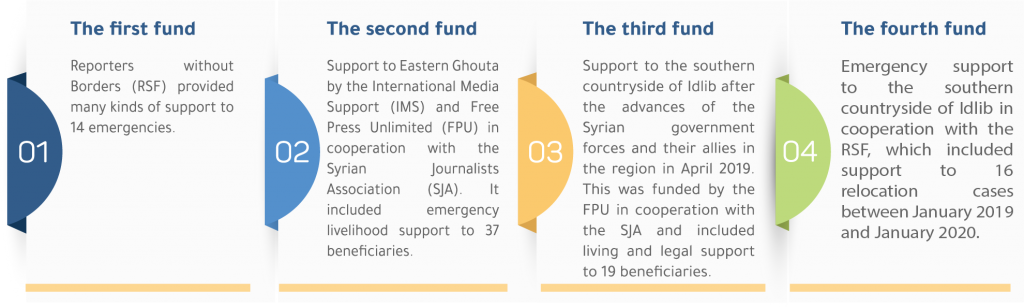

From May 2018 to August 2019, the SPD managed four emergency funds:

- Reporters without Borders (RSF) provided many kinds of support to 14 emergencies.

- Support to Eastern Ghouta by the International Media Support (IMS) and Free Press Unlimited (FPU) in cooperation with the Syrian Journalists Association (SJA). It included emergency livelihood support to 37 beneficiaries.

- Support to the southern countryside of Idlib after the advances of the Syrian government forces and their allies in the region in April 2019. This was funded by the FPU in cooperation with the SJA and included living and legal support to 19 beneficiaries.

- Emergency support to the southern countryside of Idlib in cooperation with the RSF, which included support to 16 relocation cases between January 2019 and January 2020.

2- Support to institutions:

The program received 48 technical, financial, digital, and legal support applications from local media institutions and platforms. Eight of them got financial support, one got advocacy and mobilization support, four got legal support and 12 got digital and technical support. Three applications were rejected and five others are still under consideration by international organizations. The SCM is currently working on four applications. Eleven files were closed because the applicant institutions could not survive due to poor funding.

Based on the aforementioned figures and data, the report identifies the reasons behind weak support and the efforts exerted in this regard specially to support cases of displacement and safe relocation for emergency reasons related to the safety and security of media professionals and human rights advocates in Syria. The displacement cases require greater efforts to survey numbers and assess needs. Therefore, the verification of such applications takes more time. The reasons also include the international donor criteria and to what extent they take the exceptional situations of Syria into account. Moreover, the SCM does not have enough funds to provide direct support even after verifying that the applications meet the support criteria.

In the end, the report makes a number of recommendations which aim to make the support process more effective and sustainable. These include providing journalists with protection equipment and supporting and building the capacities of local emerging media platforms and media development initiatives and institutions in all Syrian regions especially in the conflict zones. This includes funding operational costs, covering the costs of the funding application process and the financial management of institutions, training courses, and related administrative units since they are key sources of information, especially during the military escalation periods, and covering the costs of protection equipment.

II- Methodology

The report adopted the quantitative, statistical, and descriptive approach by analyzing the data of the “supportapplication forms“ received by the SCM between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2020. The numbers of all (accepted, rejected, and supported) applications were extracted from the SPD and classified under nine categories.

Using this method, the applications were divided between those received from Syria and those received from other Arab and foreign countries. The data and figures show the number of applications received by the SCM and those supported by international organizations, which all remained anonymous, with highlighting the gender distribution of applications in each category. The report uses the same methodology to evaluate the beneficiaries’ feedback forms filled by to 102 supported media professionals.

III- Introduction

With the outbreak of popular protests in Syria, the Syrian government realized the risks of professional coverage of the protests by credible independent media institutions which influence the local, regional, and international public opinion. To highlight its narrative that all the peaceful demonstrators in 2011 were terrorists and to prevent any other narratives from surfacing, Bouthaina Sha’baan, the political and media adviser to the President, explained in a press conference in March 2011 the government media policy, saying that the “Syrian Television is the only media outlet that tells the truth”.

Therefore, the government was keen on tightening its security grip to prevent regional and international journalists from entering the country. It also silenced local journalists through arbitrary detentions and killings under torture according to many reports by local and international human rights organizations including the SCM. The government targeted activists and media professionals directly in many Syrian cities such as Homs in 2011 including Mazhar Tayyara and Anas Al-Tarsha and raided the SCM headquarters and arrested all of the staff in February 2012.

In an article published by the Committee to Protect Journalists, Paul Wood, BBC correspondent in the Middle East said about his work in Syria in 2011 covering the country’s largest popular protests against the government and the regime:

“Getting caught was a real risk. There was always a government checkpoint nearby. Informers, we were warned, were everywhere.”

Wood added what he had heard from a Syrian activist about the fate of detained journalists:

An activist told me that a Lebanese reporter for an international news agency had been arrested and tortured for a month with electric shocks. A Western journalist was detained and badly beaten, her captors urinating on her as she lay on the cell floor, he said. As anyone reporting from Syria will tell you, the activists sometimes exaggerate, but such stories seemed alarmingly plausible. They were in line with what we’d heard about others who had run into trouble in Syria. The uprising was still quite new and it seemed the authorities were trying to scoop up activists’ networks by arresting journalists. The reporters who were detained for meeting with opponents of the regime were in the country legally. At the very least, we thought, we would be jailed as spies if caught. Our interpreter expected he would be killed”.

The developments in Syria made the local journalists and media activists the sole source of information in the country, especially after the government started targeting the foreign reporters directly including the attack on Baba Amro Media Center on February 22, 2012 which killed Marie Colvin, the military correspondent for The Sunday Times, and Rémi Ochlik, a military photographer. Reporters had to enter Syria illegally as the Syrian government denied them the required visas.

Impunity for the Syrian government crimes against journalists encouraged the other parties to the conflict to commit all forms of violence against them including murder and all the perpetrators of these crimes have gone with impunity till this moment.

Covering Syria’s developments was necessary, but the price was high for the local and foreign journalists and media activists. They became direct targets for the different parties to the conflict. For example, James Foley, an American journalist, was killed by ISIS in August 2014.

With the absence of any government protection mechanisms and lack of direct access for international mechanisms, the SCM and a number of Syrian institutions emerged as key liaison points between the Syrian journalists and media activists and the international institutions specialized in protecting and supporting journalists such as Freedom House, Free Press Unlimited (FPU), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Rory Peck Trust, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders (EMHRE), Urgent Action Fund (UAF) and International Media Support (IMS) to alleviate the incurred damage through support that can protect journalists and enable them to continue their work.

IV- Protection of Journalists

The International Humanitarian Law (IHL) guarantees the journalists in the areas of conflict full protection of deliberate targeting and the effects of direct military operations as they are civilians as long as they are not directly involved in the hostilities. This protection is detailed in the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions and it is not limited to the direct protection from the impact of military action. Article 80 of this Protocol provides that member states should integrate the international conventions on journalist protection into their national laws and “give orders and instructions to ensure observance of the Conventions and this Protocol, and shall supervise their execution.” To spread knowledge about the protection laws and prevent using ignorance of the IHL as an excuse for violations, the Common Article 144 of the Geneva Conventions and Article 83 of Additional Protocol I provide that “The High Contracting Parties undertake, in time of peace as in time of armed conflict, to disseminate the Conventions and this Protocol as widely as possible in their respective countries and, in particular, to include the study thereof in their programs of military instruction and to encourage the study thereof by the civilian population, so that those instruments may become known to the armed forces and to the civilian population.”

In addition to the IHL, the Security Council issued many resolutions on protecting journalists during armed conflicts including Resolution No. 1738 of 2006 which: “Condemns intentional attacks against journalists, media professionals and associated personnel, as such, in situations of armed conflict; recalls that journalists, media professionals and associated personnel engaged in dangerous professional missions in areas of armed conflict shall be considered civilians, to be respected and protected as such; recalls also that media equipment and installations constitute civilian objects, and in this respect shall not be the object of attack or of reprisals.”

Resolution No. 2222 of 2015: Encourages the United Nations and regional and sub-regional organizations to share expertise on good practices and lessons learned on protection of journalists, media professionals and associated personnel in armed conflicts … Condemns all violations and abuses committed against journalists, media professionals and associated personnel in situations of armed conflict … Urges all parties involved in situations of armed conflict to respect the professional independence and rights of journalists, media professionals and associated personnel as civilians; and combat impunity for crimes committed against civilians, including journalists, media professionals, and associated personnel.

The UN General Assembly adopted Resolution No. A/RES/68/163 of 2013, specifying November 2 as the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists to emphasize the accountability of the perpetrators of violations against media which do not only target journalists but also the community’s right to know the truth and circulate information. International conventions including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights emphasize that the protection of journalists is not limited to the times of armed conflicts but also during peace times. They stress the right to freedom of expression, circulation of information, protection of journalists and guaranteeing their safety. The freedom of media and enabling media professionals to practice their work freely reflect the society’s plurality and different views and contribute to enhancing oversight over the authorities’ work. This is stipulated in the national constitutions and laws including the Syrian ones which guarantee minimum protection for journalists from targeting during their work. Other laws and customs regulate their relationships with media institutions and guarantee their right to compensation if these institutions do not honor their obligations including providing the training and equipment needed for protection during coverage in dangerous places or conflict areas to ensure their safety and alleviate the risks. This is highlighted in the Safety Guide for Journalists issued by RSF in February 2015. It recommends that journalists should be careful and wear helmets in the high-risk areas and that their clothes are different from the military uniforms with the words Press or TV written on them.

The national or international laws remained suspended in Syria over the conflict years including the report period due to the subjective weakness of the IHL provisions and absence of enforcement mechanisms that can force the parties to conflict to implement them and impose penalties on violators and due to fact that the parties to the conflict including the Syrian government have consistently ignored the laws and targeted journalists. This made the media work impossible in many cases. Syria has, for years, been labeled among the world’s most dangerous areas for journalism, which doubles the journalists’ need for support and protection and creates responsibilities and burdens on the civil society and related institutions beyond their human and financial capacities to reduce deficiency and provide forms of support and protection for media workers facing major challenges due to the dangerous and complicated circumstances in the country.

V- Journalist Definition

The biggest challenge facing the institutions supporting and protecting journalists including the Journalist House is adopting a definition of journalists and media professionals; a key factor in accepting applications, verifying eligibility against the strict international standards for eligible journalists with the exceptional circumstances in Syria. The SCM deeply believes that all people have the right to express themselves through media not only media professionals and those considered qualified and appropriate. Obligatory requirements might restrict the freedom of expression, limit it to a certain group and obstruct the flow of information. However, the complicated situations in Syria and the intention of the Journalist House team to develop mechanisms that guarantee the highest response made it necessary to use a clear definition of journalists as a foundation for journalists and media professionals eligibility and to exclude applications submitted by civil activists, aid workers and other individuals who had limited media contributions and hence do not meet the donor criteria despite their crucial efforts to alleviate the tragic humanitarian situation in Syria.

The SCM uses the journalist definition provided for in Article 2(a) of the Draft Convention of Protection of Journalists Engaged in Dangerous Missions in Areas of Armed Conflict that is “Any correspondent, reporter, photographer, and their technical film, radio and television assistants who are ordinarily engaged in any of these activities as their principal occupation.” This definition is used for documenting and monitoring violations against media and media professional. However, the complicated circumstances under which the SPD is working in Syria made it necessary to use a less strict definition, which is more responsive to such circumstances. Thus, it opted for a narrow definition rather than the sticking to the general requirements provided for in the General Comment No. 34 of United Nation Human Rights Committee: “A function shared by a wide range of actors, including professional full-time reporters and analysts, as well as bloggers and others who engage in forms of self publication in print, on the internet or elsewhere”.

The flexibility in dealing with the strict definition was because such a definition does not cover some special cases including people who volunteered to provide continuous and professional media coverage for years though media work is not their primary profession or source of income. Thus, the SCM team processed the applications on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration the circumstances and nature of media work and ensuring that they meet the minimum requirements and criteria. Many determinants were adopted including those related to media professionals and others related to the media institutions and platforms. Those included publishing content in media outlets incessantly for no less than one year and excluding the posts on social media and personal websites.

VI- SCM Work

Based on its motto “words are our right and defending them is our duty”, the SCM has, since its establishment in 2004, been keen on providing all forms of support to journalists and media professionals to improve the level of protection and push for better media and legal work environment that guarantees protection for free, professional and independent media. SCM achieved that through monitoring the performance of media and freedoms in Syria, launching advocacy campaigns, supporting political prisoners and media workers who are harassed because of their work through defending them in courts and demanding fair trials for them and all political prisoners in Syria or through advocacy and mobilization to demand their immediate release and providing all forms of support for them and their families.

The outbreak of protests in Syria in March 2011 imposed a different media reality. Citizen journalists emerged as the most important source of information in the conflict areas due to the circumstances on the ground. “The same citizen journalists who developed their capacities, used simple tools and worked in journalism despite the many violations committed against them”. After 2012, the situation on the ground changed greatly; the de facto authorities proliferated and the number of media professionals doubled. Therefore, the scale, nature and frequency of violations committed against them increased. According to the SCM report “Syria: Black Hole for Media Work”, there were 1,670 violations between March 2011 and end of 2020. In addition, the needs doubled and with it the role of civil organizations supporting media work. There were no legal frameworks to protect media professionals or active associations to protect their rights in most of the areas outside the control the Syrian government.

This made the SCM expand its support through the Journalist House Project which is part of the Media and Freedoms Program. This Project coordinates closely and directly with the Syrian and international institutions supporting journalism, to ensure standard criteria for all support cases and build the capacity of the Syrian media sector to survive through protection mechanisms and build a comprehensive support platform for media professionals and freedom advocates that is capable of meeting their needs and enabling them to develop their tools, provide alternative solutions to improve the protection of journalists and ensure a safe work environment in accordance with the relevant international laws, adopt better laws for journalists and combat impunity.

Part 1: Support and Protection Department

As a top priority since its establishment, SCM developed its response to the needs of media professionals and human rights advocates in Syria as part of the Journalist House Project. The SPD refers and coordinates the applications process to accelerate getting support for beneficiaries and prevent duplication, provide legal support and advocacy in coordination with partners and manage the emergency funds. Support is provided after reviewing the applications submitted via the SCM website and verifying two key points:

- The applicant is a journalist, media professional or affiliated with a media institution.

- The application is directly related to the media work.

These two criteria are fundamental in all local and international organizations while other criteria vary from one institution to another. As a Syrian institution, the SCM, through its various projects under the Media and Freedoms Program in general and the Journalist House Project in particular, does its best to convey the voice of Syrian journalists to the international organizations supporting journalists and addressing dozens of cases every day.

To achieve this purpose, the SPD has worked since its establishment on key pillars:

1- Building a network of collaborators to ensure the best needs assessment in Syria in general and in the conflict zones in particular as well as effective communication with the media groups and platforms.

2- Mapping the media professionals and media institutions and platforms operating in the areas exposed to violence or displacement through surveys to enable the SPD to intervene in emergencies, after understanding the situation on the ground and assessing the best possible responses. These surveys are updated on a regular basis and verified in case of emergencies such as the one in eastern Ghouta and displacement operations in March and April 2018 and the siege of media professionals in Qunietra and Deraa in southern Syria in July 2018 and the subsequent displacement to northern Syria. There are also special surveys during the Turkish military operations in northern Syria such as the one launched in October 2019.

3- Strengthening trust between the SPD and the Syrian media professionals in the issues related to assistance, advocacy and support, to enhance the SPD support tools in accordance with the situation on the ground.

4- Coordinating with Arab and international organizations supporting media professionals in Syria through processing the applications they receive immediately to avoid duplication.

5- Coordinating with the Syrian partners including institutions and individuals.

6- Upgrading the support application form through including questions that enable journalists to introduce themselves and their work and identify the link between the required support and their media work. In 2020, the SCM started designing a special program for support cases.

7- Developing software, work tools and data platform to ensure the highest degree of privacy and safety of beneficiaries and confidentiality of their data.

8- Developing the response criteria to ensure they are compatible with the agreed criteria among the organizations and adaptable to the Syrian situations where many definitions for media professionals arise.

8- The SCM considers the digital security and protection of beneficiary data a top priority and a trust-building tool. In this context, the SCM provided digital security support to individuals and institutions directly through different programs or indirectly through the international institutions.

The differences in the number of applications in each support category and from one year to another reflect the changing situations of the media workers under to the military and political developments in Syria.

Building on the above criteria, the SPD processed 2,165 applications received from Syrian media professionals in cooperation with 11 international organizations between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2020.

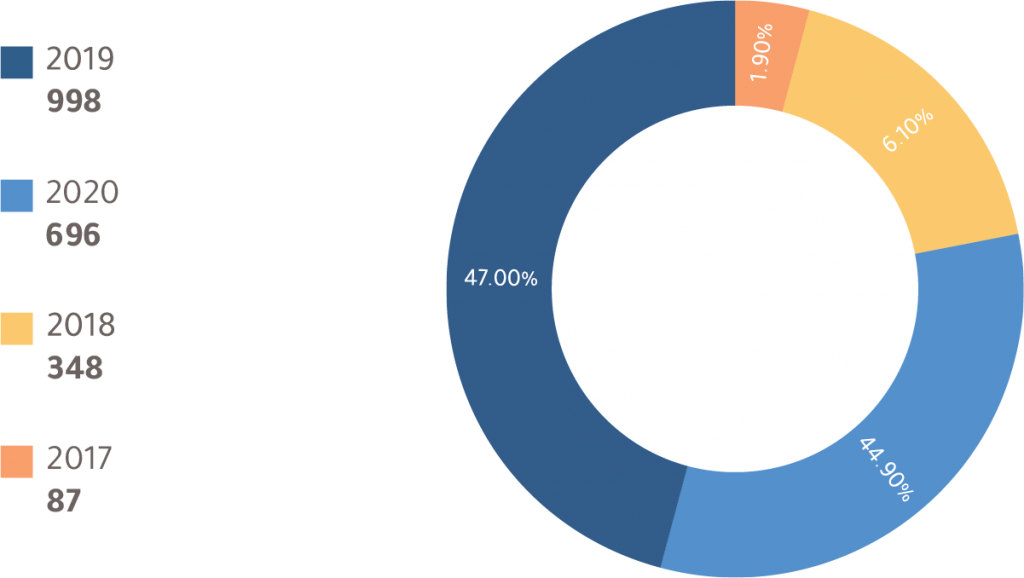

I- By Years

The numbers of support applications in each category reflect the circumstances that media workers in Syria endured and are still going through and how these numbers and support categories varied over the years due to the military and political developments. The livelihood support applications increased in the last few years due to the semi-stable and frozen conflict and the economic and living pressures in different areas of influence and control in Syria.

The number of livelihood, technical and safe relocation support applications came behind the asylum support applications, which ranked the highest throughout the four years covered by this report.

The number of applications:

(2020)

In 2020, the SCM received 104 safe relocation support applications and 323 asylum support applications as larger numbers of media workers in the conflict zones lost faith in political solution and the possibility to stay and work in journalism especially after the progress of government forces, the return of freedom restrictions to most Syrian areas, the difficult living conditions and the deterioration of health and education services.

Given the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in this year, the SMC received 148 livelihood support while the number of medical support applications fell to nine due to the declining intensity of military operations. There were 48 technical support applications.

(2019)

The year 2019 witnessed the largest number of support applications in many categories.

First, the SCM received the highest number of livelihood support applications (363) and the highest number of medical support applications (29). The main reasons include the relative cessation of hostilities and the increased awareness of the support being provided to media professionals in Syria. The SCM also received the highest number of technical support (76).

In the same year, the SCM received 96 safe relocation applications and 338 asylum applications due to the progress of government forces towards the last opposition stronghold, Turkey’s increased intervention in the Syrian territories and poor governance of the military factions controlling Idlib Governorate. There were 128 applications requesting relocation to Europe or at least to Turkey as a safe place for living.

(2018)

The report highlights the high number of livelihood support applications in 2018 as the SCM received 78 applications. There were also 44 asylum applications, technical support (15), safe relocation support (12) but only 11 medical support applications due to the great contribution of Syrian aid institutions especially medical support.

(2017)

In 2017, the country was still in the grip of the violence of the government forces, oppositions factions and terrorist groups such as ISIS. The SCM received 29 technical support applications and 17 livelihood support applications.

Despite military escalation in all regions in 2017, the SCM only received 14 asylum support applications and 13 safe relocation support applications. That was mainly because the media professionals lacked awareness of the available support opportunities. In 2017, the SCM received five medical support applications only due to the violent military operations which reduced the ability of media professionals to get in touch with the support institutions. The medical relief and civil rescue teams were busy providing immediate support to civilians.

II- By Kind of Support:

A- Support to Individuals:

To provide support that satisfy the increasing needs, the SCM adopted clear mechanisms for applications processing and support provision for those meeting the eligibility criteria published on the SCM website:

- The applicant is working in the media sector.

- The reason for requesting support is related to working in journalism.

- The applicant has continuously published content in media outlets for no less than one year.

- The published content respects the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and does not include violence, hatred or discrimination based on race, religion, gender, sect or nationality.

- The applicant should not have stopped media work for more than one year from the application date.

- The applicant should be working in institutions or organizations whose main activity is not in the media field.

- The applicant should not have received the same kind of support from another organization within six months from the date of the application submission.

The applications were classified under nine categories:

1- Asylum support: this type recorded the highest number of applications in the four years covered by the report.

With the increasing area of military operations, the security prosecution of media professionals by all the parties to conflict in Syria, there were very few safe havens for journalists. As the situation in the neighboring countries was not any better due to the economic and legal conditions, the fears of forced deportation to Syria, lack of stability because of the immigration laws in these countries, hundreds of media professionals submitted asylum applications from inside and outside Syria, seeking new opportunities for living in security and stability far from the deportation fears and restriction of the freedom of journalism. The SCM received safe relocation and asylum support applications from all Syrian regions regardless of the controlling powers including Damascus, Rural Damascus and Deraa after the government forces regained control of the governorate.

There are two types of responses: The SCM either provides the applicant with a letter of recommendation or statement clarifying their media work, the violations committed against them, their current situation and risks or cooperates with the international institutions including the RSF which played a prominent role and showed quick and effective responses to the cases in which there were direct risks to the applicants’ lives. The global refugee crisis especially after 2015 particularly in Europe increased the presence of the far-right parties which oppose refugees, in the parliaments of hosting countries. This had a negative impact on the possibilities of approving this kind of support applications.

These faced many additional obstacles including:

- Among the key criteria in prioritizing the asylum applications for countries or organizations alike are the risks associated with media work in the country of asylum regardless of the journalist’s former work or violations committed against them; the economic and legal difficulties facing most of the refugees living in the asylum countries not only journalists; and level of safety in Syria’s neighboring countries.

- The high exceptions of applicants. For example, some applicants submit their asylum applications to the SCM rather than to the relevant countries and consider that the SCM or partner organizations have their say in deciding on the asylum applications.

- Most of the countries interested in hosting refugees and the organizations supporting asylum seekers focus on refugees based in neighboring countries rather than inside Syria.

- The asylum requirements in the international law. Although Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution,” and the 1951 Refugee Convention defines the refugee as “any person outside their country of origin or the country of their nationality …” It considered this requirement one of the general conditions for recognizing the refugee status without any exceptions. Thus, the Syrians living inside Syria are excluded from the resettlement programs and covered only by special international protection programs in some European countries which receive limited numbers under specific conditions.

- The long periods required to process applications and the growing pressures over media professionals in their places of residence especially after Covid-19 pandemic, which forced many embassies and consulates to work remotely and under complicated circumstances.

- Some media professionals quitted the media work after receiving repeated threats based on their previous media work.

- The requirements of many international institutions exclude the media professionals who took part in the military work.

It is not easy to overcome the previous issues and meet the required criteria and at the same time support the eligible media professionals to reach a safer place and continue their media work. Therefore, the SCM is trying to clarify transparently that the decision is made by the authorities of the relevant countries. In the applications received from inside Syria, the SCM works on securing safe relocation for those facing risks while explaining that countries have their own immigration policies and strategies and hence the decision is theirs. The safe relocation applications are processed accordingly. The SCM demonstrates, through letters of recommendation or statements, the risks of the economic and legal situation in Syria and its repercussions on the asylum seekers in case they are deported.

The SCM received 719 asylum support applications:

- 370 applications from ten governorates inside Syria with Idlib taking the lion’s share (59.46%) followed by Aleppo (20.54%). The SCM accepted 33 applications and referred them to international institutions which supported all of them.

- 349 applications from 11 countries outside Syria, with the largest percentage being from Turkey (76.50%). The SCM accepted 224 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported 166 of them.

Figure 1: Number of asylum support cases inside and outside Syria.

The figure shows the number of asylum support applications approved by five international organizations. The SCM and RSF jointly supported 81 applications.

2- Safe Relocation Support:

The safe relocation conditions are not different from those of the other kinds of support. However, the level of emergency and the need for quick intervention are key characteristics in these cases. Journalists might be exposed to direct and specific danger where they reside and thus need to be relocated to a safe place.

The team processes this kind of applications after verifying the accuracy of their information and shares them with the partner organizations to secure financial support that helps the applicants relocate safely. It also provides the applicants with digital and physical security tips.

Providing this kind of support faced many obstacles including:

1- The high expectations of applicants.

2- The failure of applicants to implement the relocation plan due to the difficult security situations in Syria.

The team always explains transparently its role and available response opportunities for each category of support, especially safe relocation. It also follows up the applicant status to update it on a regular basis and clarify the situation on the ground to the supporting entities.

The SCM received 225 safe relocation support applications:

- 199 applications from 10 governorates inside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Idlib (64.32%). The SCM accepted 55 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported 34 of them.

- 26 applications from outside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Turkey (61.54%). The SCM accepted nine applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported all of them.

Figure 2: Number of safe relocation support cases inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of safe relocation support applications approved by seven international organizations and seven cases supported by the SCM.

3- Livelihood Support:

During the report period, situations on the ground changed dramatically. The area of military operations expanded and the government forces regained control of the areas which were until recently outside its control (Eastern Ghouta, Southern Damascus, Southern Syria, Eastern Qalamoun, Northern Countryside of Homs, Madaya and Barada Valley Regions). This triggered major displacements to Northern Syria. The media professionals had no choice as the progress of the government forces and its allies increased the risks of arresting or killing them due to their anti-government media work.

In addition, there were forced displacement waves due to the advances of the Turkish military operations in Northern Syria including in October 2019 or due to internal clashes between the Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement in Western Countryside of Aleppo in January 2019.

On the other hand, relocation to Syria’s neighboring countries was not the ideal solution due to the poor legal and living conditions given the lack of residency or protection documents which increases the risks of deportation. The difficulties of getting work permits in most neighboring countries prevented the sustainability of the media professionals’ work as well as the use of their expertise accumulated during their work under exceptional circumstances in Syria, except in very few cases. It is worth mentioning that any attempts to establish media platforms in the neighboring countries of Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey and finding independent jobs often face funding difficulties, inability to secure sustainable support and legal obstacles though in the first years of conflict, these countries were the best place for the alternative Syrian media.

On the other hand, the media professionals inside Syria continued to work under terrible circumstances including poor wages, great risks working in one of the most dangerous regions for media professionals, weak protection and lack of protection equipment such as helmets and vests and lack of job opportunities due to weak and unsustainable funding. All of this made most of the media institutions unable to endure their long-term financial or moral commitments.

The outbreak of Covid-19 in 2020 made matters worse. Despite the decline of military operations, the global health situation had a negative impact on the Syrian media professionals due to the lack of job opportunities and work difficulties under the pandemic restrictions.

In light of this reality, the SCM received 608 livelihood support applications in the period 2017-2020.

Due to the large number of applications, providing this kind of support faced many obstacles including:

1- The high expectations of applicants given the harsh circumstances they are undergoing.

2- Some international organizations do not consider the risks facing media professionals unique and believe that they are related to the general humanitarian situation (a humanitarian crisis and general living and legal circumstances which all people suffer from).

3- The growing needs vis-à-vis poor capacities and limited response and support opportunities at the SCM and even at the international institutions.

4- Discontinuing media work. Although in some cases, applicants were harassed and are facing security prosecution, most international institutions consider that this, at best, contradicts the requirement of continuous media work.

5- Logistic difficulties due to the complicated military situation in Syria, tight security grip in most of the areas and the need for international institutions to comply with strict European financial policies and criteria.

The Journalist House team tried to address these challenges and problems through:

1- Providing transparent clarifications to the applicants about the SCM role, capacities and the chances of approval.

2- Explaining to the interested and supporting organizations that the potential risks facing media professionals are not general; the media work opposing any of party to conflict entails high risks including abuse, deportation, detention, killing, etc.

3- Identifying the level of emergency in each application based on the data (emergency cases requiring livelihood or financial support, the existence of a special medical status etc.).

4- Highlighting the continuous risks though in some cases, the media professionals have quitted this field of work.

5- Following up the applicants and sharing the available opportunities for continuing working in the media field.

6- Clarifying the current situation and logistic difficulties inside Syria and finding appropriate solutions for each case.

The SCM received 608 livelihood support applications:

- 491 applications from 11 governorates inside Syria with Idlib taking the lion’s share (74.75%) followed by Aleppo (17.92%). The SCM accepted 134 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported 105 of them.

- 117 applications from outside Syria (Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq, Germany and France), with the largest percentage received from Turkey (81.20%). The SCM accepted 62 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported 30 of them.

Figure 3: Number of livelihood support cases inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of livelihood support applications approved by nine international organizations and 37 applications supported by joint funds between the SCM and RSF in 2018-2019.

4- Technical and Equipment Support:

The technical support applications came fourth after the livelihood, asylum and safe relocation. Despite the crucial importance of the other kinds of support, the technical support is key as it contributes to the continuity of income generation opportunities required for the sustainability of media work.

The loss of media equipment due to confiscation or damage during the armed conflict is among the key problems facing media professionals in Syria because the employers do not provide equipment or because these professionals work as freelancers. Although the SCM believes that the media professionals inside Syria should be prioritized and their expertise should be leveraged, providing technical support and equipment to media professionals even after they reach safe places (including Europe) is important as well.

Although equipment is crucial to the sustainability of media work, the poor funding of technical equipment was among the major problems facing the team in processing this type of applications. Despite the team’s attempts to share prioritized applications coming from emergency areas with the highest needs, there was no response to this kind of applications.

The SCM received 168 technical and press cards support applications:

- 146 applications from nine governorates inside Syria with Idlib taking the lion’s share (65.07%) followed by Aleppo (20.55%). The SCM accepted 13 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported three of them.

- 22 applications from six countries, with the largest percentage received from Turkey (50%). The SCM accepted six applications, but the international institutions did not support any of them.

Figure 4: Number of technical and equipment support cases inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of technical and equipment support applications approved by four international organizations.

In addition, the program started, since its establishment, looking for ways to provide journalists with protection equipment including helmets and vests as they very necessary for the media work and the employer institutions do not provide them. Such equipment is crucial and, in many cases, makes the difference between life and death especially in light of the expanding military operations and targeting civilians and residential areas where media professionals are covering daily incidents. Despite the direct targeting of hundreds of media professionals during the military operations, the SCM could not provide physical protection equipment. Most of those professionals, whether inside or outside the government-controlled areas, did not receive sufficient training and awareness on media coverage in armed conflicts.

However, press cards were provided as protection means as they are supposed to facilitate work and prevent detention and targeting. The SCM provided five cards, two issued by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) through cooperation with the IMS in 2017 and three issued by the UPF. The SCM has been cooperating with the Syrian Journalistic Association (SJA) on press cards issued by the IFJ and it is currently working on the issue in France through the UPF.

5- Medical Support: (Contacting medical facilities or covering the costs of medical treatment):

Journalists working in conflict areas, whether independent or under the command of military units or war correspondents, often receive special training on media coverage during armed conflicts and they are provided with occupational safety equipment. Employers often consider threats in the workplace when determining wages and other contractual arrangements. All of this is not available to the Syrian media professionals. In a time when media outlets could not deploy trained correspondents on the ground, there emerged the role of the citizen journalists and local media platforms and initiatives which became the main source of information. This meant that media volunteers and professionals were subject to all kinds of violations including physical abuse during their media work. The SCM documented 222 injuries among media professionals between 2011 and 2020 (see the report “Syria: Black Hole for Media Work”). These numbers reflect the extremely dangerous and complicated field situations and require medical support. The Journalist House provided support in contacting medical facilities or covering the costs of medical treatment through supporting organizations.

Providing this kind of support faced many obstacles including:

1- Difficulty to verify whether the injury happened during the media work due to the lack of accurate and professional documentation.

2- High costs of medical treatment and the need, in some cases, for quick intervention that was obstructed by the bureaucracy of international organizations.

3- Media work might aggravate some medical issues such as weak eyesight, back problems and chronic diseases, which might in turn affect the work sustainability and in both cases the requirement that the injury happens during the media work is not met.

4- Lack of treatment for some cases inside Syria.

5- The need for medical support is often accompanied with the need for livelihood support during the treatment period when no other sources of income are available.

6- Inability to support the applicants whose media work caused them permanent disabilities due to the inability to provide them with prosthetic limbs, the continuous need for support and inability to resume their media work due to their disabilities.

7- Illegal residency in some countries impedes the possibility of getting medical treatment.

The Journalist House team tried to solve these problems through:

1- When media and legal documents are not available, additional verification is carried out through collaborators and contact and reference persons to confirm that the injury happened during the media work.

2- Cooperating with Syrian and international medical organizations to secure treatment from outside the institutions supporting the media.

3- Communicating with the medical organizations inside Syria to help get medical referrals based on the needs.

4- Cooperating with the medical organizations and securing financial support through the media support organizations.

5- Looking for medical organizations to make prosthetic limbs to help media professionals resume their work.

The SCM received 54 medical support applications:

- 29 applications from three governorates inside Syria, with the lion’s share of applications received from Idlib (75%). The SCM accepted 21 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported 20 of them.

- 25 applications from three countries, with the lion’s share received from Turkey (88%). The SCM accepted seven applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported all of them.

Figure 5: Number of livelihood support cases inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of medical support applications approved by five international organizations.

6- Employment Support:

The work team focuses on sharing the available job opportunities with the applicants whether those in the SCM, organizations or media outlets.

The SCM received 89 employment support applications:

- 67 applications from eight governorates inside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Idlib (49.74%). The SCM accepted and supported 54 applications.

- 22 applications from outside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Turkey (86.36%). The SCM accepted 17 applications and referred them to the international institutions but they approved none.

7- Legal Support:

The legal needs of media professionals varied along the report period. Accordingly, there were many response levels. These starts with providing legal consultations by the SCM legal office, Arab legal organizations or legal experts in the relevant countries and bringing cases to justice through appointing specialized lawyers.

According to the report “Syria: Black Hole for Media Work”, 140 journalists were disappeared and 434 faced arbitrary detention due to media work over the period of ten years, not to mention the journalists killed under torture during detention. As the international laws and conventions on journalist protection are not respected by all the parties to the conflict especially the Syrian government and due to the absence of the rule of law and fair trials in most Syrian areas, the support and assistance opportunities seem limited as the applicants are either disappeared, under arbitrary detention or tried before exceptional courts especially the Field Military Court. Following up and dealing with such cases is easier when addressed by courts that allow the presence of defense lawyers.

Providing this kind of support faced many obstacles particularly on the level of accessing justice:

1- Some of the problems facing media professionals working in media institutions are related to employment rights and contractual obligations. Thus, they are not specific to the media work but are more connected to the rights of employees and work issues and most of the media support organizations do not cover such issues.

2- The media professionals’ dire need for work and the absence of protection entities or frameworks force them to accept unjust contracts regardless of their legal knowledge.

The SCM included in its future action plan raising the awareness of media professionals about their legal rights, improving the legal environment of media work and contracting lawyers from all Syrian cities to provide the required legal support.

The SCM received 17 legal support applications:

- 10 applications from two governorates inside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Idlib (90%). The SCM accepted seven applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported all of them.

- 12 applications from five countries, with the largest percentage received from Turkey (25%). The SCM accepted seven applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported three of them.

Figure 6: Number of legal and advocacy support cases inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of legal and advocacy support applications approved by four international organizations and three cases supported by the SCM.

8- Advocacy Support:

Advocacy is a support tool that uses the best networking ways to communicate the cause to the relevant organizations and entities for lobbying and getting the best possible support. The SCM received and responded to two advocacy support applications, one from inside Syria and the other from Turkey.

Despite the importance of advocacy, its direct results might be totally unclear due to the lack of respect for the international laws and conventions on the protection of journalists.

9- Other types of support:

This category includes the applications not included in the previous eight categories such as study completion, specific trainings and supporting the asylum applications of the journalists’ families. The applications and response options are evaluated based on the available capacities and the SCM rejects many applications which are not within its mandate.

The SCM received 57 applications in this category:

- Six applications from four governorates inside Syria, with the largest percentage received from Idlib (61.5%). The SCM accepted 11 applications and referred them to the international institutions, but they did not support any.

- 18 applications from outside Syria, with the largest percentage received from France (50%). The SCM accepted 10 applications and referred them to the international institutions which, in turn, supported three of them.

Figure 7: Support applications under the “Other” category received from inside and outside Syria

The figure shows the number of applications under the “Other” category approved by three international organizations.

Emergencies – Forced Displacement:

The SCM addressed a number of emergency cases resulting from the military and political developments which undermined the space for media work and, directly or indirectly, threatened media workers in those areas. It used the available resources i.e. liaising between the applicants and international organizations.

In the period from May 2018 to August 2019, the Journalist House Program facilitated four emergency funds:

- The first fund was provided by RSF. It supported 14 emergency cases.

- The second fund was allocated to Eastern Ghouta with the support of the International Media Support (IMS) and Free Press Unlimited (FPU) in cooperation with the Syrian Journalists Association (SJA). It provided emergency support to 37 beneficiaries.

- The third fund was allocated to the southern countryside of Idlib with the support of FUP and in cooperation with SJA. It supported 19 cases.

- The fourth fund was provided by RSF. It was allocated to individuals and institutions from January 2019 till the end of 2020. It supported 29 cases.

The program addressed cases of siege and forced displacement which media workers faced through collaborators on the ground in different areas. Lists of the names of media workers in the areas which faced forced displacement (Deraa, Eastern Ghouta, Homs, Idlib, Rural Damascus and Southern Damascus) were prepared.

1- Deraa and Quneitra: 2018

The SCM followed up the siege of media professionals in Quneitra and Deraa in June 2018. It prepared an initial list of the names of besieged media professionals and pressured to secure their safe exit. During that period, a military settlement was reached between the government forces and the opposition factions, leading to the displacement of 67 media professionals to northern Syria in July 2018.

Resettlement and supporting the asylum applications of displaced people from southern Syria:

In the context of the above-mentioned incidents, from the list containing 67 displaced media professionals, 42 resettlement applications were supported between July 2018 and July 2019 in cooperation with RSF, CPJ and RSF-Germany.

Livelihood Support to Displaced Media Professionals from Southern Syria:

55 applications from the list received livelihood support in Turkey through RSF, CPJ, Freedom House and IMS. Twelve applications from the list have not received any livelihood or resettlement support yet and the applicants are still in northern Syria.

II- Displaced Media Professionals from Eastern Ghouta: Ghouta Emergency Fund 2018

The SCM monitored the military operation launched by the government forces in Eastern Ghouta, which led to the displacement of a large number of media professionals and activists to northern Syria,

In May 2018, the Journalist House managed the Eastern Ghouta Emergency Fund which was funded by the IMS and FPU in cooperation with the SJA. The program received 122 applications. It supported 37 livelihood/financial applications, referred 35 applications to the Response Coordination Group which included international organizations that support media professionals and rejected 50 others because the applicants could not prove their work in the media field or did not meet the eligibility requirements.

III- Emergency in Idlib: 2019

This was allocated to the north west of Syria after the progress of the government forces and their allies in the region.

The southern countryside of Idlib and northern countryside of Hama have witnessed major military escalation by the government and Russian forces since April 2019. This caused the displacement of many media professionals to relatively safe areas in the city of Idlib and its northern regions. In this context, the project updated the general survey of media professionals in Idlib Governorate in cooperation with the Free Media Support Association (ASML). Their total number reached 450. In addition, the project is surveying the media professionals who are still living in the areas of military operations. It started preparing a response plan in cooperation with the partner organizations to resettle displaced media professionals and provide them with livelihood support.

The SCM established a joint fund in cooperation with the SJA and FPU to provide financial support. The fund supported 19 applications. With the continuous emergency and displacement of media professionals whose lives are in danger due to their media work, resettlement lists were prepared in cooperation with the RSF and 17 applications were approved. However, three of the accepted applicants did not complete the safe relocation procedures for personal reasons. They were distributed as follows:

- Two cases to Luxembourg. They were transferred to Turkey and then to Luxembourg.

- 12 cases to Germany. Nine were transferred to Turkey and then to Germany.

- Two cases to Lithuania.

B- Support to Media Institutions:

According to the SCM report “Mapping the Syrian Media” after the outbreak of protests in Syria, the number of emerging media outlets and initiatives reached 600 in the period 2011-2015, of which only 160 continued until 2019.

A key challemge facing media outlets is the funding difficulties and lack of sustainability due to the absence of sustainable support and institutional work as most of them are local initiatives and platforms established during the armed conflict. Due to the legal restrictions hindering the media work and the extremely hostile security environment, most of these institutions are unlicensed and have no internal regulations or work contracts. In light of the current circumstances, these outlets proposed themselves as an alternative to the government media which remained for a long time the only source of information. However, some of these alternative media outlets lack expertise and professionalism. They lack the tools needed to ensure their continuity. The media platforms established after the outbreak of protests were in most of the cases the only source of information from the areas of conflict and the ones not covered by the media. Like the “citizen journalist” phenomenon, they emerged because the objective circumstances required alternative media to communicate information, document violations and present an alternative narrative of the incidents.

All of the above was only part of the challenges facing the team in supporting and assisting media institutions. However, the SCM believes in the importance of supporting these initiatives and their independence; improving their level of professionalism; taking into consideration the criteria related to the kind of discourse and media professionalism; respecting the International Declaration of Human Rights; avoiding violence incitement and spreading hate speech; influence on audience; type and frequency of publishing; gender sensitivity and ensuring organized institutional work. However, the weak support sources and continuous needs in the long term prevent achieving that as the available support is mostly temporary and has limited impact. Only few of the media institutions established after 2011 managed to survive and sustain their media work.

During the report period, the program received 48 technical, financial, digital and legal support applications from local media institutions and platforms. They were distributed as follows:

- Financial support: The SCM received 16 financial support applications, of which eight got support as a result of cooperation between the SCM and RSF and EMHRE. Three applications were rejected and five ones are yet to be decided on.

- Advocacy and mobilization support: One media institution was supported in March 2017.

- Legal support: Four media outlets were supported.

- Digital security support: The SCM enhanced the digital security of six media institutions and platforms and provided them with technical support.

It is worth mentioning that among the 15 institutions which the SCM was reviewing their applications, 11 local media platforms stopped working due to the changed situation on the ground and the applications of four institutions are still being processed.

III- Gender-related Comments:

The gender distribution among the nine categories of the applications which met the support requirements and those which did not, was as follows:

Gender distribution of applications which met the requirements

Figure 8: Gender distribution of accepted applications

Gender distribution of applications which did not meet the requirements

Figure 9: Gender distribution of rejected applications

The above figures show the dominance of the applications sent by male media professionals over those sent by females (79.2% and 20.72% respectively). The percentages of applications sent by females which met the requirements in the nine categories varied from 22.5% in the employment support to 2.9% in the asylum support and the percentages of those which did not meet the requirements started from 7.6% in the livelihood/financial support. The SCM did not receive any applications in the medical and legal and advocacy support. The above-mentioned percentages highlight the weak engagement of women, which reflects their weak presence in the Syrian media landscape. The SCM is working on addressing this issue and increasing the gender balance in the Syrian media landscape. It is important to support women empowerment approaches based on participation, gender equality and management of diversity and difference. The SCM aims to develop the media work environment, take part in drafting laws and raise awareness to facilitate the women participation in the media field.

| Support type over four years | % of accepted male applicants | % of accepted female applicants |

| Livelihood support | 25.98 % | 7.07 % |

| Asylum support | 32.68 % | 2.92 % |

| Safe relocation support | 22.22 % | 6.22 % |

| Technical support | 4.16 % | 7.14 % |

| Advocacy and legal support | 47.36 | 10.52 % |

| Medical support | 46.92 % | 5.55 % |

| Other | 26.31 % | 10.52 % |

| Employment support | 57.30 % | 22.47 % |

In this context, the team focused on empowering and supporting female media workers and considering the importance of providing them with quality support and assistance to continue their work and enhance their media capacities. The Journalist House’s work team coordinated with the international organizations supporting women in particular such as the

Rights to secure emergency financial support for female media professionals in coordination with Marie ColvinJournalists’ Network. The SCM also nominated journalist Yakeen Bido for the Courage in Journalism Award for 2020 which is given by the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) upon its request and she won the award indeed.

The team provided legal support and advocacy to female media professionals who were subject to gender-based violations including blackmailing and bullying. The team is still working on improving its tools to facilitate the female media workers’ access to the best possible response to reduce violations, provide the required protection and evaluate the best available means of support.

Part 2: Evaluation of Support by the Beneficiaries

As part of the process of monitoring and evaluating the support process, the SCM sent an evaluation form in February 2021 to 102 journalists who received support from the Journalist House Project in the period 2017-2020 and asked them to evaluate the mechanisms of provided support including the response, follow-up, difficulties and impact. The SCM received 85 responses (66 from males and 19 from females).

As for geographical distribution, about half of the beneficiaries are inside Syria (49.4%) and the others are distributed as follows: 1.2% in Jordan, 2.4% in Iraq, 3.5% in Lebanon, 9.4% in Turkey, 11.8% in Germany and 22.4% in France.

The form included a question about how much the received support was relevant to their beneficiaries’ needs. 67.5% said they received relevant support and 32.5% said they did not. In light of these percentages and the reasons which might delay the provision of relevant support (such as the verification of applications and the need to respond to emergency applications), the levels of satisfaction with the SCM support came as follows:

Figure 10: Levels of beneficiaries’ satisfaction with the SCM support

The levels of satisfaction with the support process (from receiving the application until support is provided) were similar to the above levels (44.7% very high and 3.5% very low).

According to the beneficiaries, the low rates of satisfaction are due to difficulties in receiving money transfers or to insufficient support, especially technical support where equipment is more costly than the amounts they received. The highest percentage said they were very satisfied with the SCM support and response. This is due to many reasons:

- The SCM responded to their applications while other organizations they contacted did not even answer them.

- Relatively quick response to applications especially to emergencies.

- The assistance was significant and effective. (One beneficiary said that the financial support he received helped in securing housing for him and his family, treating his sister and undergoing an eye surgery).

The application form also included a question about the priorities of support to understand the urgent needs of Syrian media professionals as some of them chose more than one types of support. The responses were as follows:

- Safe relocation: (38.8%)

- Legal support: (29.1%)

- Livelihood support: (25%)

- Technical support: (20.8%)

The above percentages show that all these four categories are almost equally important. Comparison shows that the provided support was much lower than the requested support. For example, out of the 168 technical support applications, only 10 were supported which is very low in comparison with the 20.8% of beneficiaries who prioritized technical support.

Part 3: Difficulties Facing the Work Team:

- The large number of emergencies and displacement cases facing Syria media professionals as reflected in the large number of applications. This requires more efforts from the SCM team to survey numbers and assess needs. In addition, the classification of Syrian media professionals is not clear due to the situation on the ground.

- The criteria of international organizations and the extent to which they can accept exceptional situations in Syria especially those related to the operational logistics.

- The period required to provide support was not suitable for urgent applications. In some cases, the period between the organization’s approval and facilitating the support process was too long while the needs were urgent and needed quick response.

- It is necessary that the exceptional situation in Syria is taken into consideration. The media-related professional associations are marginalized or even non-existent in some areas and the many armed forces on the ground put the lives of media professionals at risk and require the CSOs to play a bigger role.

- The high number of support applications require long time to verify that they meet the requirements of the SCM and supporting international organizations, which delayed the support provision.

- Many applications did not meet the requirements. For example, the SCM received applications from people who do not work in the media field which wastes the time of the SPD team in verifying them and explaining the support mechanisms.

- The SCM does not have its own financial fund that allows it to provide direct support to eligible applicants and it does not have sufficient human resources.

- In the period between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2020, the SCM cooperated with 11 international organizations to respond to the support applications. The permanent relationship and communication between the SCM and partner organizations highlights its role, as a key and important partner in supporting the Syrian media professionals, verifying their applications and ensuring they meet the organizations’ criteria. The organizations commended the SCM performance in terms of transparency and professionalism in organizing the meetings and safe communications and making efforts to coordinate communications between the beneficiaries and the supporting organizations.

VII- Findings

After considering the aforementioned data and figures in all support categories and distribution of the accepted and rejected applications, the following points can be highlighted:

- The number of applications varied between one category and another. For example, asylum support came first with 719 applications followed by the livelihood support with 609 applications while the lowest was the legal and advocacy support with 19 applications. This indicates that the journalists’ needs are similar.

- The number of applications was very high. Over the four years, the SCM received 2,165 applications under the nine categories in addition to the emergency funds. This highlights the need of media professionals for support and the importance of local and international institutions in securing quick and long-term responses to all kinds of such needs.

- The provided support was not up to the needs of media professionals inside and outside Syria. There was great disparity between the number of received applications and that of the supported ones in all categories.

- The highest number of applications in all nine categories was received from Idlib Governorate due to many factors. Idlib is last place where media professionals can work free from the Syrian government restrictions. They gathered there after the government forces controlled their areas and displaced them. Another factor is the work difficulties due to the military clashes and tensions in the region and the harassment of media professionals by the de facto authorities. In addition, the media professionals in that area enjoy at least some freedom in communicating with the local and international institutions while the Syrian government imposes tight security grip on media professionals under its control.

- The supporting organizations have limited capacities and resources. There were only 11 international organizations supporting media professionals while the needs are larger and growing.

- The dominance of asylum applications over other kinds of support. The SCM received 719 asylum support applications and 608 livelihood support applications, the second largest number.

- The support criteria are not compatible with the urgency of needs. For example, the SCM received 146 technical support and press cards applications. Most of them requested field protection tools. However, due to the international organizations’ strict criteria which do not take Syria’s situation into consideration, only 19 applications met the criteria and only three applicants were supported.

- The support to technical applications was very weak. Figure 8 shows that the technical support category had the lowest percentage of accepted applications (7.1% males and 4.2% females) and Figure 9 shows that it had the highest percentage of rejected applications (76.2% males and 22.5% females).

- The need for continuous support in the livelihood/financial support category or providing alternative job opportunities that meet the current needs as many applicants had disabilities and they can no longer work in the media field.

- More support should be provided to the technical and protection equipment applications as 20.8% of the beneficiaries said this is a priority for them.

- The crucial role of local Syrian institutions in facilitating the support process through verifying the applications and providing the donor organizations with the required details.

- The beneficiaries are still in need for the support of donor organizations and the assistance of local institutions.

VIII- Recommendations

- Long-term support strategies are needed: The international institutions and donors should consider supporting media professionals and institutions as a sustainable process and empower journalists to rely on themselves rather than find emergency solutions for exceptional situations. Implementing sustainable media programs and projects which ensure the leverage of journalist expertise accumulated in conflicts.

- Reconsidering the criteria and requirements applied by the entities and organizations involved in protecting and supporting journalists in light of the media work developments; and establishing sustainable media programs and projects that provide livelihood support to journalists and leverage their media expertise accumulated during conflicts.

- The local institutions defending the freedom of opinion and expression should be able to provide direct support from their own funds after the applications are approved to facilitate the process of supporting the beneficiaries.

- The local media institutions should allocate sufficient resources to improve the level of protection of their employees as part of clear policies including ones for emergency response.

- The media institutions should provide a legal and professional environment that guarantees the rights of Syrian journalists and media professionals.

- Providing journalists with appropriate training and protection equipment including helmets and vests and with technical support to enable them to continue their work; otherwise, journalists might quit the media work.

- Allocating an emergency fund for the journalists working in the north east of Syria and those displaced from Afrin and Ras al-Ayn and protecting the rights of media professionals displaced from these areas.

- Combating impunity to ensure sustainability of media work in Syria as many journalists lost faith in prosecuting the perpetrators of crimes against them. Combating impunity is a national need.